Michael S. Van Leesten Biography

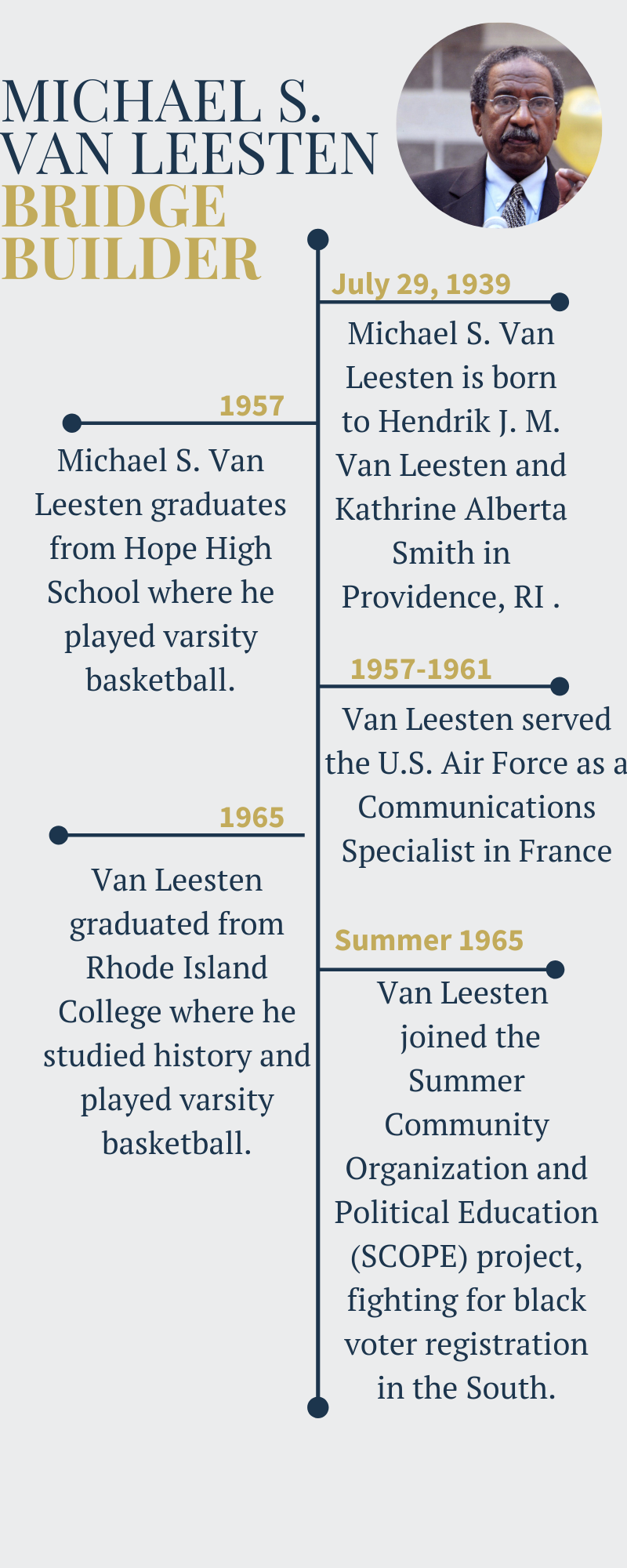

Often, a person will change through a city, but a city will rarely change through a person. Michael S. Van Leesten was such a man who left Providence a better, honest, and more just world after living within it. Born in Providence to Hendrik J. M. Van Leesten and Katherine Alberta Smith on July 29, 1939, Michael S. Van Leesten attended Hope High School and lived for a time on Doyle Avenue while it was still a majority African-American neighborhood. At a young age in Hope High School, Van Leesten pursued both his study and sports with rigor. His basketball success landed him a starring role in the varsity basketball team, playing for a time for the Benefit Street Center. Graduating in 1957, Van Leesten set his course to France to work as a communications specialist for the United States Air Force. At 22, he returned to Providence to settle into a bachelor’s degree at Rhode Island College in History. Picking up basketball at the collegiate level, he rejoined with the varsity team as a formidable player.

Michael S. Van Leesten cited his first stirrings of responsibility in the civil rights movement when he picked up reading of “the Negro Revolt” by the African-American journalist Louis E. Lomax. Soon after, Van Leesten traveled down to Alabama to promote voter registration for the first time in 1962 with colleagues from RI and various parts of the country. Coordinated by Reverend Andrew Young, a close confidant of Martin Luther King Jr., these political education and voter registration efforts served as an enlightening introduction into the civil rights struggle for Van Leesten.

While a student at Rhode Island College in 1964, he then formed the aptly named Rhode Island Students for Equality (RISE) across Providence’s foremost universities, a move exemplary of his later climb as a civil rights leader and organizer in the community. As a co-chair of the group, Van Leesten brought over John E. Maddox, president of the Providence branch of NAACP, and Irving J. Fain, co-chairman of Citizens United for a Fair Housing Law, to speak and gathered a crowd over 200 strong. Days later, Van Leesten headed a march throughout the city to support fair housing and anti-discrimination legislation, converging at the Statehouse. For months leading up to graduating RIC, Van Leesten organized and participated in protests and sit-ins throughout the city. These inspiring efforts would be the early winds in the sails of his continued fight for racial equality and justice.

Newly graduated from RIC, that motivation would manifest as Michael S. Van Leesten joined the Freedom Riders in Choctaw County, Alabama, as a part of the SCLC SCOPE initiative to register Black Southerners to vote. The group was brought over by Reverend Arthur L. Hardge and his colleague Irving J. Fain, a philanthropist who supplied the vehicles that brought them to Alabama. Together they worked in defiance of the absurd obstructionist rules in Alabama towns, dictating that black citizens could only register to vote on the first Monday of the month, from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m, often with the KKK looming. The Ku Klux Klan attempted to terrorize and intimidate Van Leesten and his colleagues. Segregationists assaulted them verbally and physically, attacking his group with pepper spray in response to their fight against voter suppression. Despite facing the wickedness of racism that summer by Van Leesten’s count, they registered over 1,000 people to vote when previously just over 100 were registered in a county of 6,000. Michael Van Leesten and the many others he traveled with planted the seeds that summer for the continued activism of an unfinished fight against voter discrimination and suppression in the South.

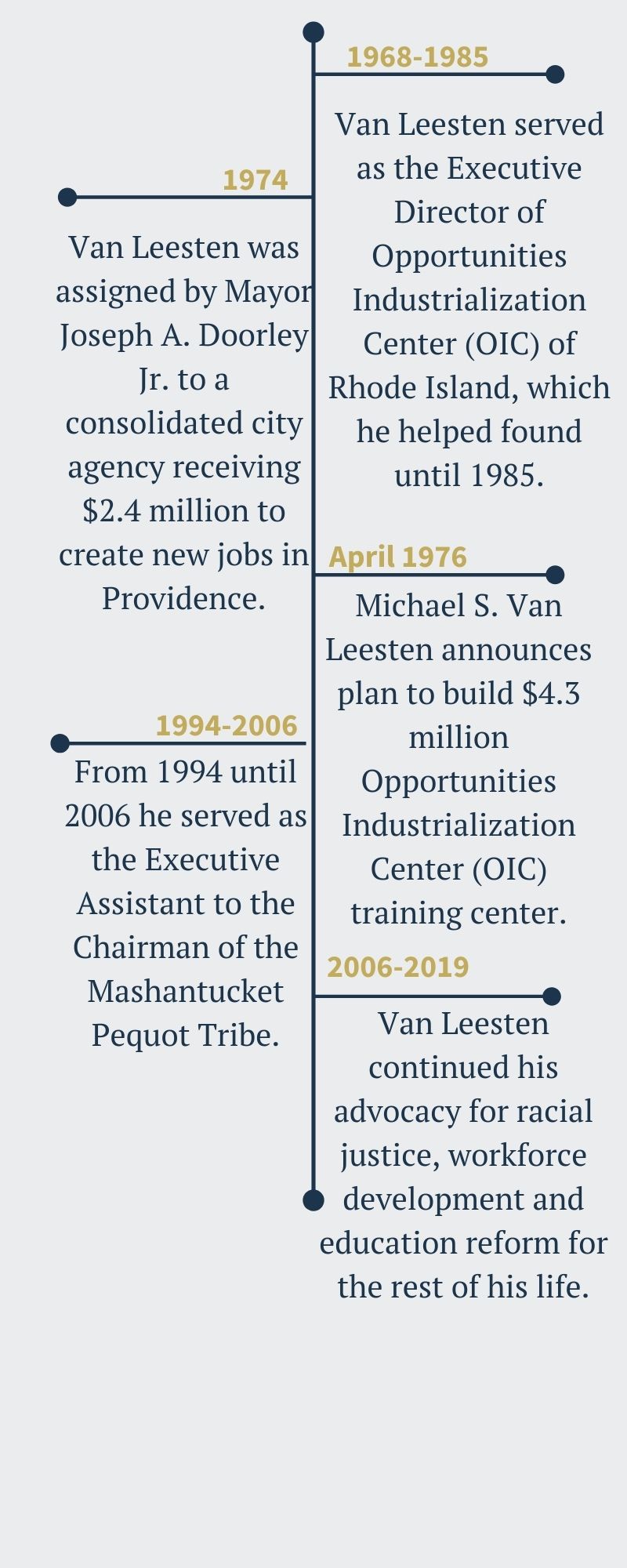

Originally intending to pursue graduate school in Mexico, Van Leesten shifted his energies to teaching in public schools with a focus on teaching African-American history. Van Leesten described his attempts to make racial justice manifest in the public-school system as a struggle of frustration and alienation from the school administration. He soon moved away from teaching towards community development. In that move, Van Leesten paired with Arthur L. Hardge from his freedom riders days to found the landmark Occupational Industrialization Center (OIC) of Providence. Starting with just $3,000 in 1968, Van Leesten grew one of the most influential minority-focused career and education centers in the city to date. A year earlier, Van Leesten was elected to the executive board for Progress of Providence, the leading anti-poverty agency in the city, while also working as president of the neighborhood non-profit corporation for the Mount Hope Redevelopment project. Busy as ever, Van Leesten nonetheless had his finger on the pulse of the city’s ailing unemployed minority population, who were being largely ignored or sidelined in discussions on fighting unemployment. For the rest of his life, Michael S. Van Leesten was to be their champion. OIC was Van Leestens vision on how to repair the gap in career opportunities and training for minorities.

During these early years of the OIC, Michael S. Van Leesten did not falter in his commitment to outing injustice. He proved this through all variations of his civil rights work, but especially in the 1970 police brutality case of Richard Metts, a young black activist in the Black Liberation School. As the spokesperson of the newly formed Coalition of Black Leadership, Michael S. Van Leesten built the foundation necessary to arrange a meeting with mayor Joseph A. Doorley and Attorney General Herbert F. DeSimone to make demands to rid the police department of unjust and discriminatory practices.

In the early 70s, while a member of the Board of Regents and field executive of the RI Commission Against Discrimination, Van Leesten was instrumental in pushing for a larger enrollment of African-Americans in higher education, particularly in his alma mater, RIC. He approached these limits of access through OIC, doubling enrollment and offering courses in mathematics, English, consumer education, minority history, and personal development. Career training courses expanded in equal measure, as Van Leesten introduced courses in air traffic control, pre-nursing, drafting, electronics, telephone training, and numerous other pre-professional classes. The OIC built training partnerships with many companies, such as New England Telephone and Brown & Sharpe Co., and in two years had trained 1,274 students, of which 779 were women. In eight years, that number had risen to 10,000.

Michael S. Van Leesten passed away on August 23, 2019. His infallible dedication to justice and patronage serves as a model for all who want to create change in their communities. In these difficult times, a new generation of leaders has come up, ready to face the battles ahead. Those who advocated for Rhode Island’s long overdue name change, the Rhode Islanders who marched in the peaceful protests honoring victims of police brutality such as George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and all who exercised their right to vote in an unprecedented election — all have honored the memory of Mr. Van Leesten by following the same playbook laid out by him and other prominent Black leaders of his time. As our nation reckons with the realities of racial injustice that still exist today, let us take time to remember the men and women like Mr. Van Leesten who came before us; the men and women who built the bridges that we have walked across.

In the Summer of 2020, the Providence City Council voted to rename the Providence Pedestrian Bridge in honor of Michael S. Van Leesten. This landmark in the City of Providence will now pay homage to a man who spent is life building bridges towards justice and equality.